The truth about missing missiles

I slept through the first cry of the gulf war of 1991, an odd achievement since my room’s window practically faced the siren. It was obscured only by the water tower, which could block its sight but not its sound. Both were planted next to each other in the sandy back lot of my elementary school five minutes or so away from our house, and both stood out plainly against the sky, high above any other building in our low roof suburban neighborhood.

I might have slept through the war’s first explosion as well if my mother hadn’t shaken me awake. There are very few moments I remember as exactly as I remember her hands on my body and the panic in her breath, and then, as she yanked me out of bed, the explosion, which took terrifying form in my mind. I saw a fat and stubby water tower of a missile pummel bright clouds of hell’s fire through blackness as it headed towards me.

The world shook around us. My mother pushed me and my younger brother into the study, which had been our designated sealed room. The room’s window was duct-taped shut and a wet towel was placed under the crack of the door as instructed by the military spokesperson; this was our protection against chemical warfare, my Israeli generation’s belated version of the 1950’s “Duck and Cover”, except for the fact that this was real, it was really happening. My mother forced the gas mask onto my face and painfully pulled at its rubber chords. Then came the silence and the waiting.

I remember the room through the mask, the jerky head movements unconsciously brought about by the narrowed field of vision, the pungent hospital smell of the black rubber, the grossly amplified sounds of our breathing, and the quiet. We were waiting for our deaths, for our invisible killer to seep in through the cracks in the walls, then through the unavoidable gaps between the mask and our skin and from there into our lungs, and the pain wouldn’t be far behind. I was ten years old and I thought “I don’t want to die”. It wasn’t the first time I’d thought about death, but it was the first time I found myself in the same room with it.

I kept checking my mask’s vacuum by covering its filter and sucking in the air until my mother slapped my hand away from it. Her voice was frighteningly muted through her mask. My nose was itchy and runny but I couldn’t get to it. I felt like crying but beat the sensations away; my father was gone on reserve duty and my mother needed us to be strong. We sat and waited for an eternity. I grew impatient with the fear, I didn’t care about missiles or deadly gasses any more, I wanted to blow my nose and eat some of the dried bananas we had on the desk. I was driving myself crazy with conversations in my mind, torn between simple, immediate urges and the overshadowing fear of death. I exhausted myself to sleep that way, leaning against the wall with snot running down my lips and the clammy skin inside my mask.

When I woke up it was over. I had slept through the second siren, the one that let us know the missile had not been a chemical one. My mother didn’t want to bother my sleep; I had curled up on the floor and seemed peaceful. She’d been able to remove my gas mask and wipe my face without waking me. I was furious at her. I had missed both of the war’s sirens; the one that went up and down to alert us of the missile in the air and the long and steady one that told us we were safe. I had gone through it without going through it. I was still in the dark.

Of course I had heard the siren before. Israel had three sirens a year during the week that preceded the Israeli Independence Day; one for Holocaust Day and two for Memorial Day, during which we stood and paid tribute to the dead, a minute of silence accompanied by a nationwide wail. But up until the war I had always heard these sirens from up close, too close in fact. I had always been at school, counting the seconds in class till the siren went off right outside our windows, its slow, moaning beginnings scaring the breath out of our lungs every time. One of those times we’d engaged in a game of marbles in the sand underneath the siren during recess, and when we returned to the game afterwards we found that several of the marbles that had been left behind had exploded from the siren’s force. It was a scare and a thrill.

The morning after the first scud missile hit Israel was a morning of panic for me. I’d never heard the siren from the distance of our house and I had no idea how loud it would be. Would I be able to hear it? Would it startle me half to death, or would it be more like a faint humming, barely louder than the buzz of the refrigerator? Every little sound made me jump; the bending of a motorcycle’s engine as it zipped by the house or the chirping of a far away bird, they all sounded like a siren for a split second.

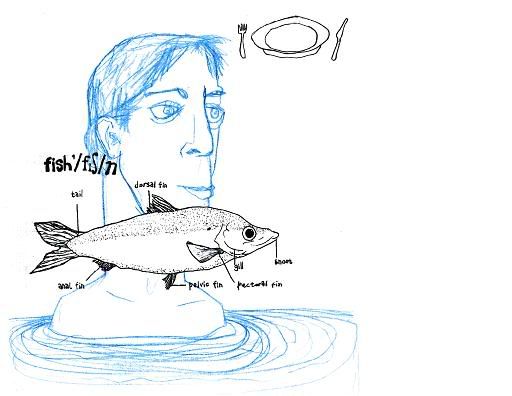

Since I had no idea what volume to expect from the siren, I fought for silence throughout the entire day. We had all the radios in the house tuned to the special war station which was dubbed “The Silent Wave”, a station that played absolutely nothing until the event of an attack, so that the radios could be turned up without interfering with our soundscape. I refrained from watching TV but caught a glimpse of the remains of the scud missile on the news. It was not as I’d imagined it; it was skinnier and longer, much longer than it had sounded. A couple of police officers lifted the bent missile and I almost laughed. It looked ridiculous.

The second missile was not as memorable as the first was. In all honesty, I can’t remember it or distinguish it from the attacks that followed over the next month or so. I remember becoming easily adjusted to our new life, enjoying the month-long break from school, nonchalantly expecting a missile every evening and laughing a lot, especially with friends or in front of the television. It was common amongst kids to sneak up behind each other, cover our mouth with our hands and imitate the steady rise of a siren. We also enjoyed imitating the radio’s war codes; which were “Viper Snake, Viper Snake” for an incoming missile, and “Heavy Heatwave, Heavy Heatwave” for the confirmation that the missile head was not chemical.

Israeli comedy shows created memorable gems during the war, a pinnacle of dark Jewish humor. Comedians acted out skits about the incompetent Iraqis and their rickety mobile missile launchers. Another comedian created a recurring fictional character of the Iraqi ambassador to Israel, who offered silly explanations for his country’s aggressions. In these skits the Iraqi soldiers weren’t the enemy, they were lovable buffoons. Saddam, however, remained evil. He was absent from the comedy shows and his face was plastered on toys that were meant to be broken or smashed against a wall. The fortunate fact that his name rhymed with the Hebrew word for ‘stupid’ lent itself to many taunting songs we sang joyfully.

A few weeks into the war my father returned home from reserve duty. He was not acquainted with our new routine, and as a result of his melodramatic reaction to his first missile with us at home I remember one more attack clearly. After the first day of the attacks we’d traded the study for the shelter and we’d become accustomed to a slow and sometimes begrudging march towards it when the siren was heard, but on my father’s first night home he ran and grabbed me and my brother with violence I’d never seen in him before and rushed us to the shelter like inanimate luggage. He practically threw us in there. Before his return we’d been sitting inside the shelter in our gas masks feeling stupid until the word came that all was clear. With our father we had to sit through his rocking back and forth and mumbling “I thought my kids would never see another war.”

As if that was war. Once I’d gotten over my initial brush with death I’d started craving war, real war, not this nightly joke that was going on around us. The fear was gone. The subsequent explosions were not as loud or as frightening as the first had been, they felt distant and remote. The siren wasn’t too loud and it wasn’t too low, it was no more exciting or terrifying than a car alarm down the street was. The threat of chemical warheads on the missiles was potent for the first week, but was lost on a child’s erratic attention span by the second week.

My parents were scared. My mother rarely showed it, but my father had a flare for drama and always let his emotions lead him. He was a large man who cried and laughed with the same lack of shame. We were living in the most dangerous area in Israel during the war, where the majority of missiles fell. We never thought of leaving before my father had come home, but once he was back we were packed and off to the relative safety of friends of the family in Jerusalem within a couple of days. During our second night there a missile fell less than thirty feet away from our home and claimed the single life that was lost due to a direct hit. The war knew many second hand deaths, heart attacks and gas mask malfunctions, but only one man was crushed to death by his shelter’s steel door when the missile hit his house.

I could not believe that I had missed it. The whole war had been for that moment, yet I hadn’t even heard a siren. It was exactly why my father had taken us away from there, and I felt I would never forgive him. I begged to come along the next day to inspect the damage to our house. I was allowed there only after my father had cleaned up all the glass, and so I never got to see any of that either. When I got there all I saw was that most of our roof tiles had been blown away, that none of our windows had any glass in them and that every single window frame was bent up as if it had an erection. Our dog was crying. I overheard my father telling his sister that the dog was covered in glass when he found him and shivering in a panic.

My dog was irreparably traumatized by the war. I stared at him in envy. He’d gotten to be there and witness it all, he’d felt the ground shake and the glass against his fur. I already knew that I wanted to be a storyteller, and as one war was the best thing that could ever happen to me. I would use the expending of other’s ammunition as my own ammunition. All I was left with now was the pale story of missing the missile. Of course, I could always lie, but that wasn’t it. I’d wanted more than a story; I wanted the presence of death, up close and yet still at bay, liked a caged predator at the zoo. I’d felt the fear, now I wanted its rewards.

And it must have been even more than that, because other than the frustration I felt faced with the minor destruction of our windows and doors and the heart wrenching whimpers of our poor dog, I was choking on guilt. I not only deserved to be there as a reward, I deserved it as punishment as well. I was guilty and I was ashamed. Missing a war is a strange and sick weight to carry around, and I would feel it again and again, especially when the missiles returned to Israel’s skies. The horrid headlines fired up a homesickness in me that I could never explain to others. I couldn’t even explain it to myself.

I might have slept through the war’s first explosion as well if my mother hadn’t shaken me awake. There are very few moments I remember as exactly as I remember her hands on my body and the panic in her breath, and then, as she yanked me out of bed, the explosion, which took terrifying form in my mind. I saw a fat and stubby water tower of a missile pummel bright clouds of hell’s fire through blackness as it headed towards me.

The world shook around us. My mother pushed me and my younger brother into the study, which had been our designated sealed room. The room’s window was duct-taped shut and a wet towel was placed under the crack of the door as instructed by the military spokesperson; this was our protection against chemical warfare, my Israeli generation’s belated version of the 1950’s “Duck and Cover”, except for the fact that this was real, it was really happening. My mother forced the gas mask onto my face and painfully pulled at its rubber chords. Then came the silence and the waiting.

I remember the room through the mask, the jerky head movements unconsciously brought about by the narrowed field of vision, the pungent hospital smell of the black rubber, the grossly amplified sounds of our breathing, and the quiet. We were waiting for our deaths, for our invisible killer to seep in through the cracks in the walls, then through the unavoidable gaps between the mask and our skin and from there into our lungs, and the pain wouldn’t be far behind. I was ten years old and I thought “I don’t want to die”. It wasn’t the first time I’d thought about death, but it was the first time I found myself in the same room with it.

I kept checking my mask’s vacuum by covering its filter and sucking in the air until my mother slapped my hand away from it. Her voice was frighteningly muted through her mask. My nose was itchy and runny but I couldn’t get to it. I felt like crying but beat the sensations away; my father was gone on reserve duty and my mother needed us to be strong. We sat and waited for an eternity. I grew impatient with the fear, I didn’t care about missiles or deadly gasses any more, I wanted to blow my nose and eat some of the dried bananas we had on the desk. I was driving myself crazy with conversations in my mind, torn between simple, immediate urges and the overshadowing fear of death. I exhausted myself to sleep that way, leaning against the wall with snot running down my lips and the clammy skin inside my mask.

When I woke up it was over. I had slept through the second siren, the one that let us know the missile had not been a chemical one. My mother didn’t want to bother my sleep; I had curled up on the floor and seemed peaceful. She’d been able to remove my gas mask and wipe my face without waking me. I was furious at her. I had missed both of the war’s sirens; the one that went up and down to alert us of the missile in the air and the long and steady one that told us we were safe. I had gone through it without going through it. I was still in the dark.

Of course I had heard the siren before. Israel had three sirens a year during the week that preceded the Israeli Independence Day; one for Holocaust Day and two for Memorial Day, during which we stood and paid tribute to the dead, a minute of silence accompanied by a nationwide wail. But up until the war I had always heard these sirens from up close, too close in fact. I had always been at school, counting the seconds in class till the siren went off right outside our windows, its slow, moaning beginnings scaring the breath out of our lungs every time. One of those times we’d engaged in a game of marbles in the sand underneath the siren during recess, and when we returned to the game afterwards we found that several of the marbles that had been left behind had exploded from the siren’s force. It was a scare and a thrill.

The morning after the first scud missile hit Israel was a morning of panic for me. I’d never heard the siren from the distance of our house and I had no idea how loud it would be. Would I be able to hear it? Would it startle me half to death, or would it be more like a faint humming, barely louder than the buzz of the refrigerator? Every little sound made me jump; the bending of a motorcycle’s engine as it zipped by the house or the chirping of a far away bird, they all sounded like a siren for a split second.

Since I had no idea what volume to expect from the siren, I fought for silence throughout the entire day. We had all the radios in the house tuned to the special war station which was dubbed “The Silent Wave”, a station that played absolutely nothing until the event of an attack, so that the radios could be turned up without interfering with our soundscape. I refrained from watching TV but caught a glimpse of the remains of the scud missile on the news. It was not as I’d imagined it; it was skinnier and longer, much longer than it had sounded. A couple of police officers lifted the bent missile and I almost laughed. It looked ridiculous.

The second missile was not as memorable as the first was. In all honesty, I can’t remember it or distinguish it from the attacks that followed over the next month or so. I remember becoming easily adjusted to our new life, enjoying the month-long break from school, nonchalantly expecting a missile every evening and laughing a lot, especially with friends or in front of the television. It was common amongst kids to sneak up behind each other, cover our mouth with our hands and imitate the steady rise of a siren. We also enjoyed imitating the radio’s war codes; which were “Viper Snake, Viper Snake” for an incoming missile, and “Heavy Heatwave, Heavy Heatwave” for the confirmation that the missile head was not chemical.

Israeli comedy shows created memorable gems during the war, a pinnacle of dark Jewish humor. Comedians acted out skits about the incompetent Iraqis and their rickety mobile missile launchers. Another comedian created a recurring fictional character of the Iraqi ambassador to Israel, who offered silly explanations for his country’s aggressions. In these skits the Iraqi soldiers weren’t the enemy, they were lovable buffoons. Saddam, however, remained evil. He was absent from the comedy shows and his face was plastered on toys that were meant to be broken or smashed against a wall. The fortunate fact that his name rhymed with the Hebrew word for ‘stupid’ lent itself to many taunting songs we sang joyfully.

A few weeks into the war my father returned home from reserve duty. He was not acquainted with our new routine, and as a result of his melodramatic reaction to his first missile with us at home I remember one more attack clearly. After the first day of the attacks we’d traded the study for the shelter and we’d become accustomed to a slow and sometimes begrudging march towards it when the siren was heard, but on my father’s first night home he ran and grabbed me and my brother with violence I’d never seen in him before and rushed us to the shelter like inanimate luggage. He practically threw us in there. Before his return we’d been sitting inside the shelter in our gas masks feeling stupid until the word came that all was clear. With our father we had to sit through his rocking back and forth and mumbling “I thought my kids would never see another war.”

As if that was war. Once I’d gotten over my initial brush with death I’d started craving war, real war, not this nightly joke that was going on around us. The fear was gone. The subsequent explosions were not as loud or as frightening as the first had been, they felt distant and remote. The siren wasn’t too loud and it wasn’t too low, it was no more exciting or terrifying than a car alarm down the street was. The threat of chemical warheads on the missiles was potent for the first week, but was lost on a child’s erratic attention span by the second week.

My parents were scared. My mother rarely showed it, but my father had a flare for drama and always let his emotions lead him. He was a large man who cried and laughed with the same lack of shame. We were living in the most dangerous area in Israel during the war, where the majority of missiles fell. We never thought of leaving before my father had come home, but once he was back we were packed and off to the relative safety of friends of the family in Jerusalem within a couple of days. During our second night there a missile fell less than thirty feet away from our home and claimed the single life that was lost due to a direct hit. The war knew many second hand deaths, heart attacks and gas mask malfunctions, but only one man was crushed to death by his shelter’s steel door when the missile hit his house.

I could not believe that I had missed it. The whole war had been for that moment, yet I hadn’t even heard a siren. It was exactly why my father had taken us away from there, and I felt I would never forgive him. I begged to come along the next day to inspect the damage to our house. I was allowed there only after my father had cleaned up all the glass, and so I never got to see any of that either. When I got there all I saw was that most of our roof tiles had been blown away, that none of our windows had any glass in them and that every single window frame was bent up as if it had an erection. Our dog was crying. I overheard my father telling his sister that the dog was covered in glass when he found him and shivering in a panic.

My dog was irreparably traumatized by the war. I stared at him in envy. He’d gotten to be there and witness it all, he’d felt the ground shake and the glass against his fur. I already knew that I wanted to be a storyteller, and as one war was the best thing that could ever happen to me. I would use the expending of other’s ammunition as my own ammunition. All I was left with now was the pale story of missing the missile. Of course, I could always lie, but that wasn’t it. I’d wanted more than a story; I wanted the presence of death, up close and yet still at bay, liked a caged predator at the zoo. I’d felt the fear, now I wanted its rewards.

And it must have been even more than that, because other than the frustration I felt faced with the minor destruction of our windows and doors and the heart wrenching whimpers of our poor dog, I was choking on guilt. I not only deserved to be there as a reward, I deserved it as punishment as well. I was guilty and I was ashamed. Missing a war is a strange and sick weight to carry around, and I would feel it again and again, especially when the missiles returned to Israel’s skies. The horrid headlines fired up a homesickness in me that I could never explain to others. I couldn’t even explain it to myself.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home